What are Symbols Music Note?

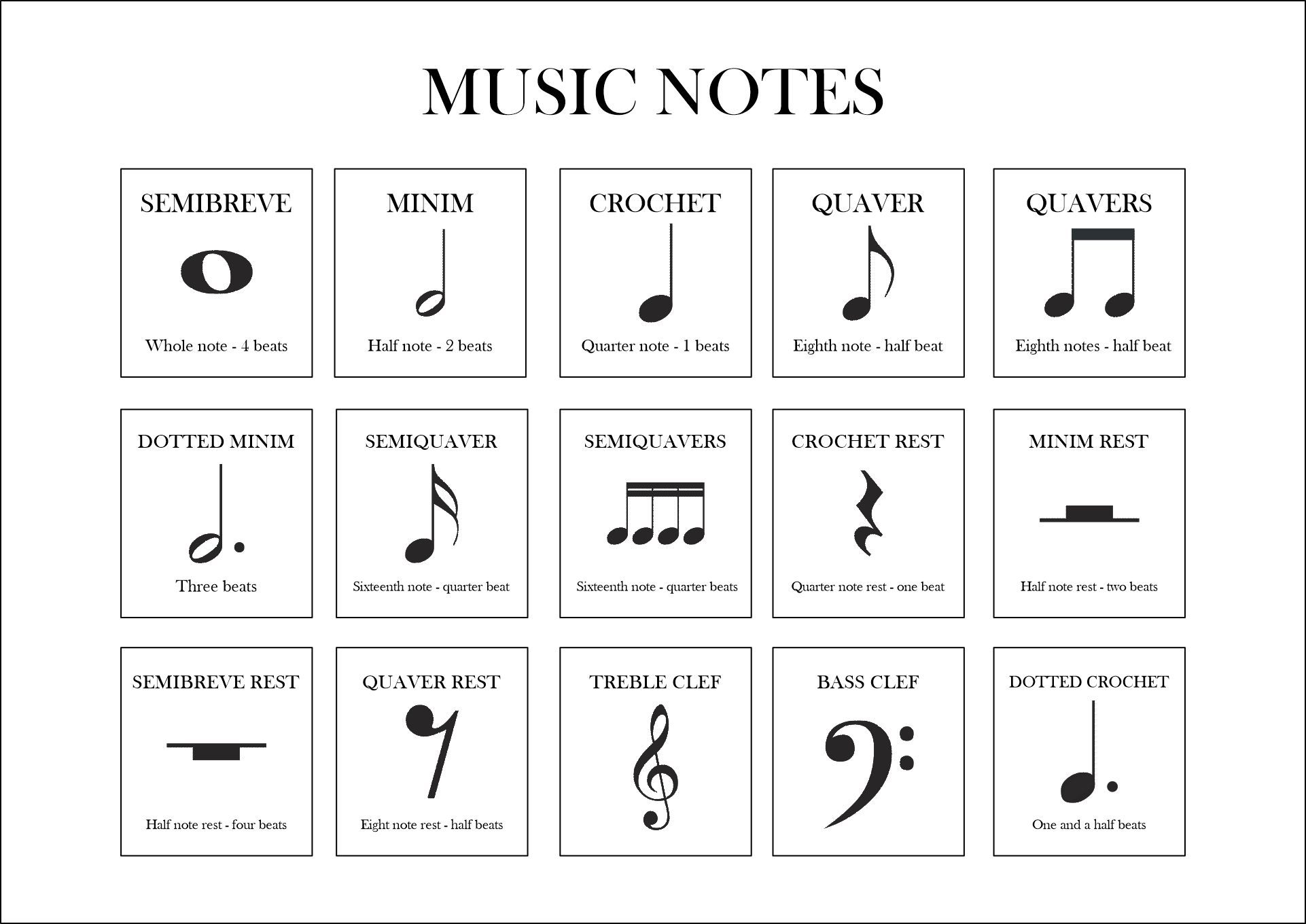

Symbols Music Note are signs and symbols used in musical notation. Their function is to indicate important elements or aspects in a musical composition. These symbols communicate information about various important elements in music such as pitch, dynamics, duration, tempo, form, detail, and articulation.

Symbol music notes are written in lines. Some types of lines are staff, ledger, bar line, double bar line, bold double bar line, dotted bar line, brace, and bracket.

Symbol music notes also use clefs. Clefs are keys used to set a particular note on one line of the stave. Clefs are effective keys for defining the range of notes. Examples of keys are bass, treble, alto, and tenor.

Music note symbols must use musical notation. Music notation represents the length of the note to the whole note. For example, a half note is ½ a whole note and a quarter note is ¼ a whole note.

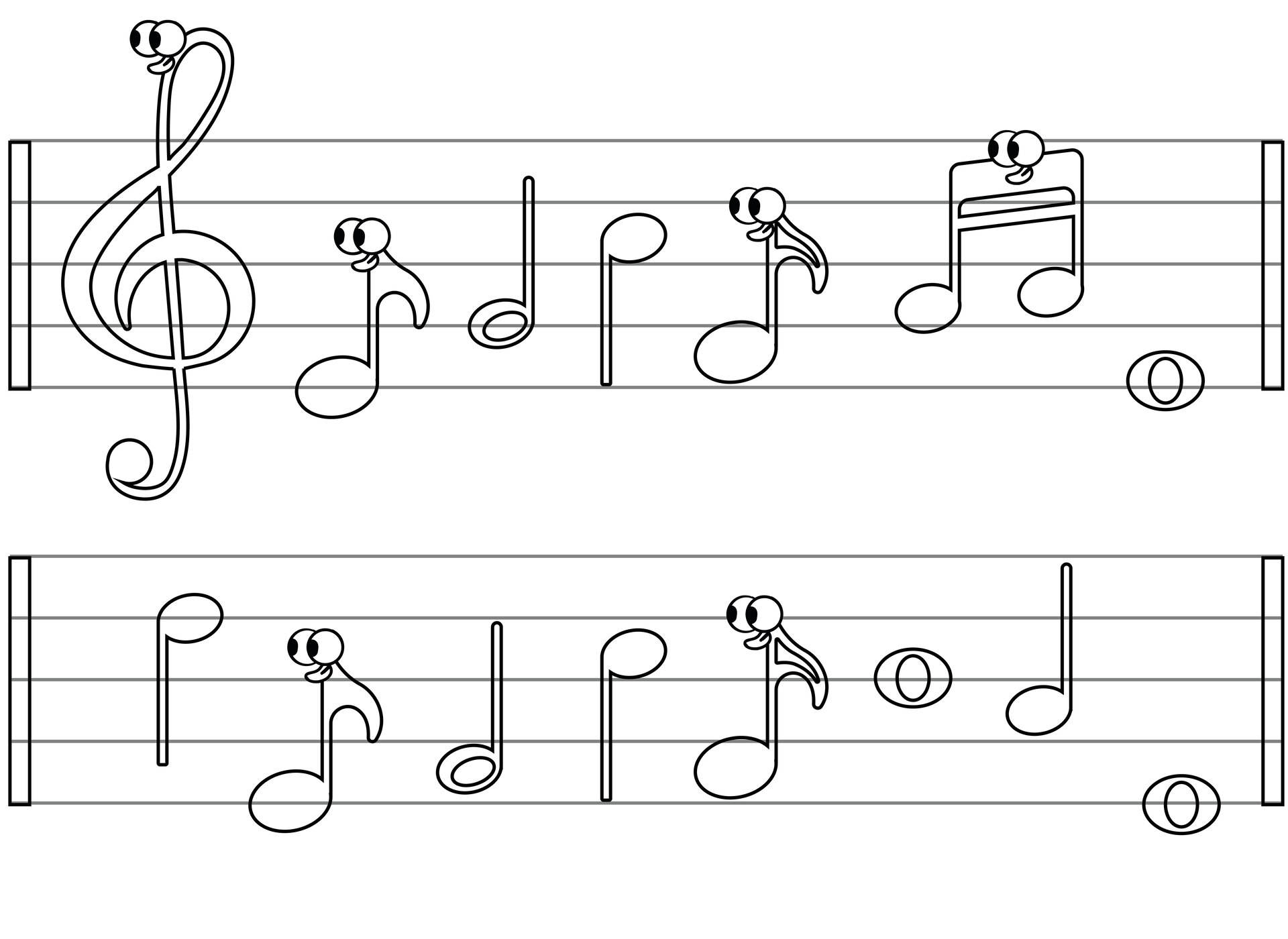

Music Notes Coloring Pages Printable

Music Notes Coloring Pages Printable

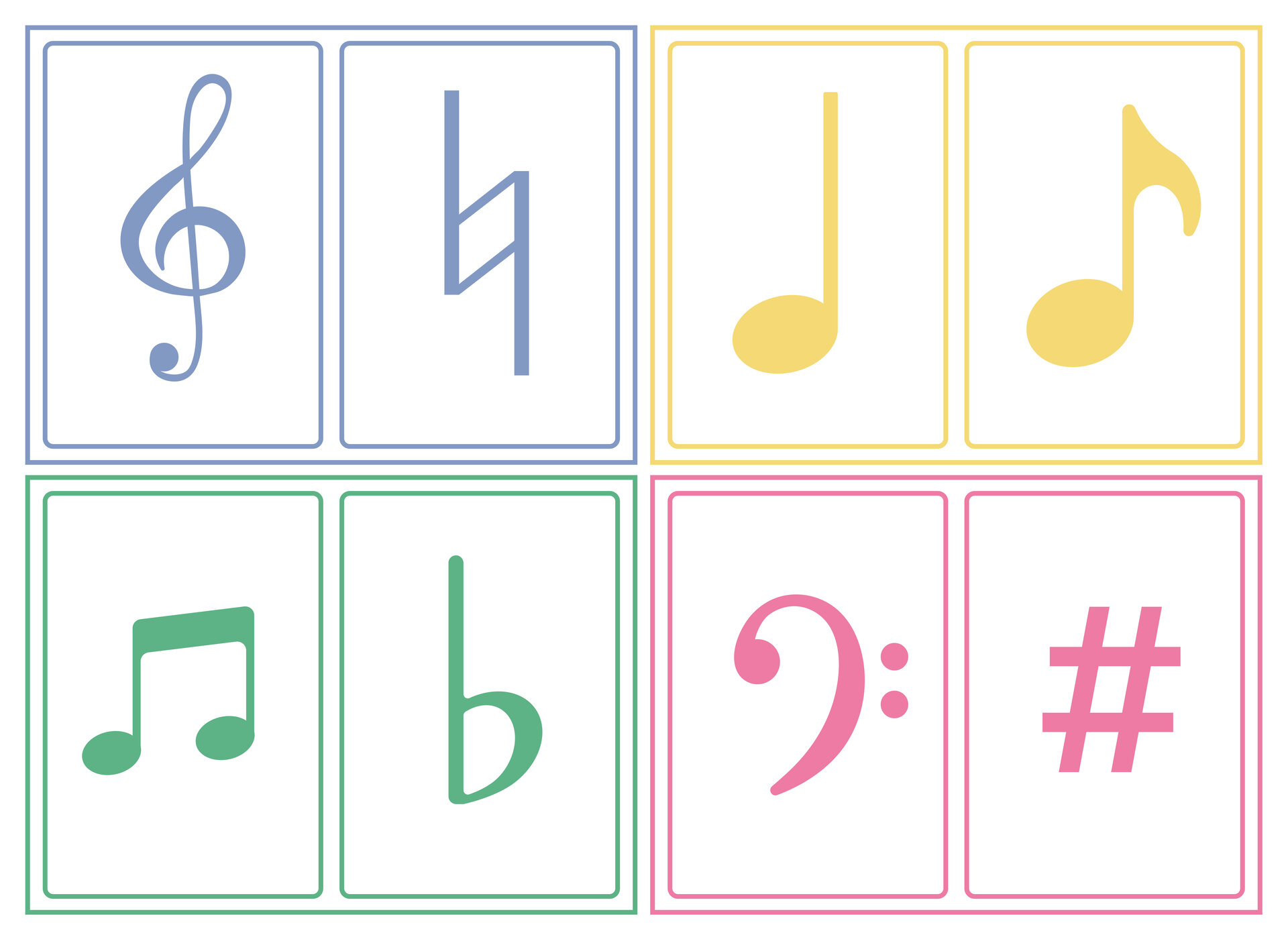

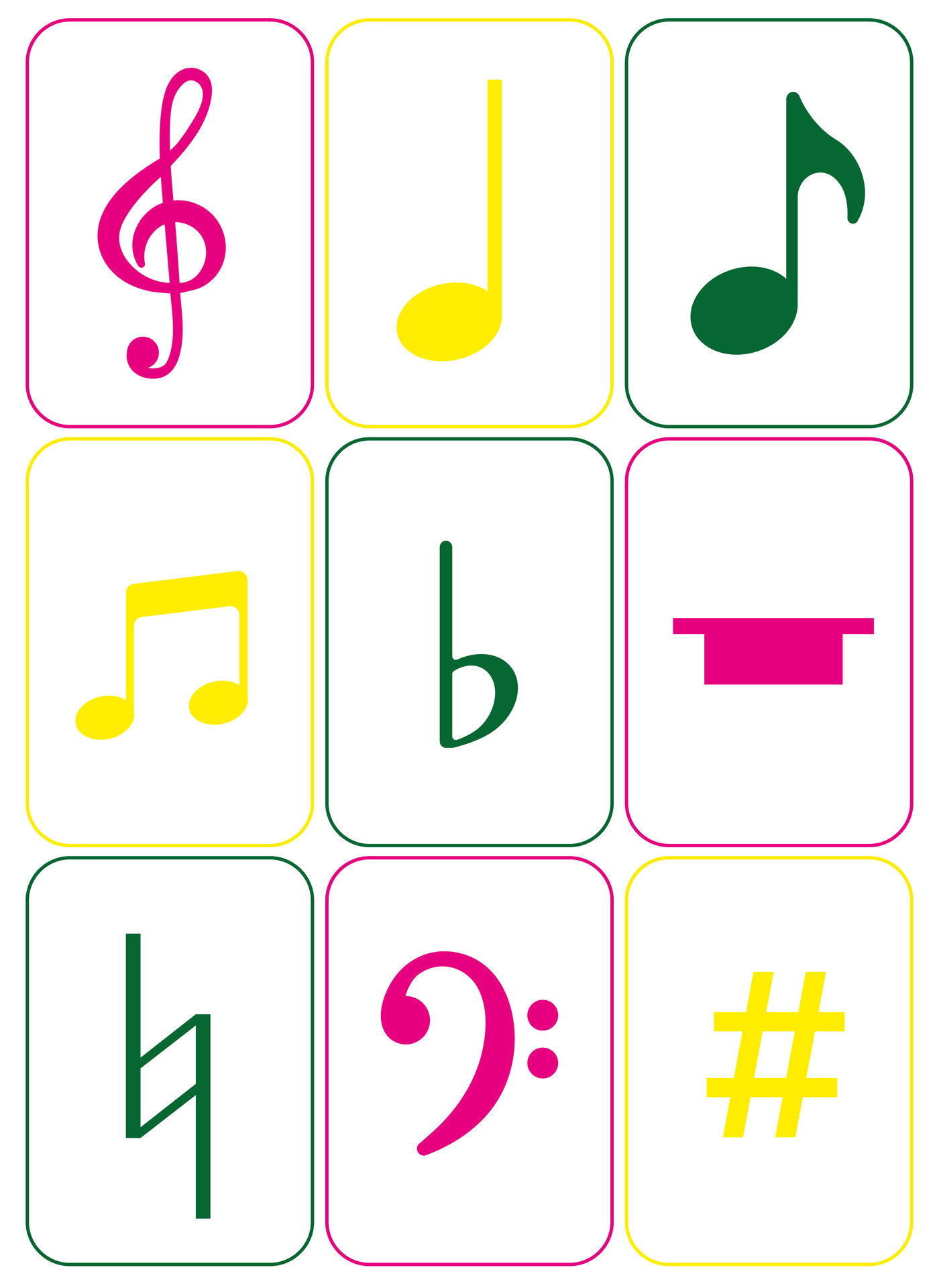

Art Clip Musical Music Notes

Art Clip Musical Music Notes

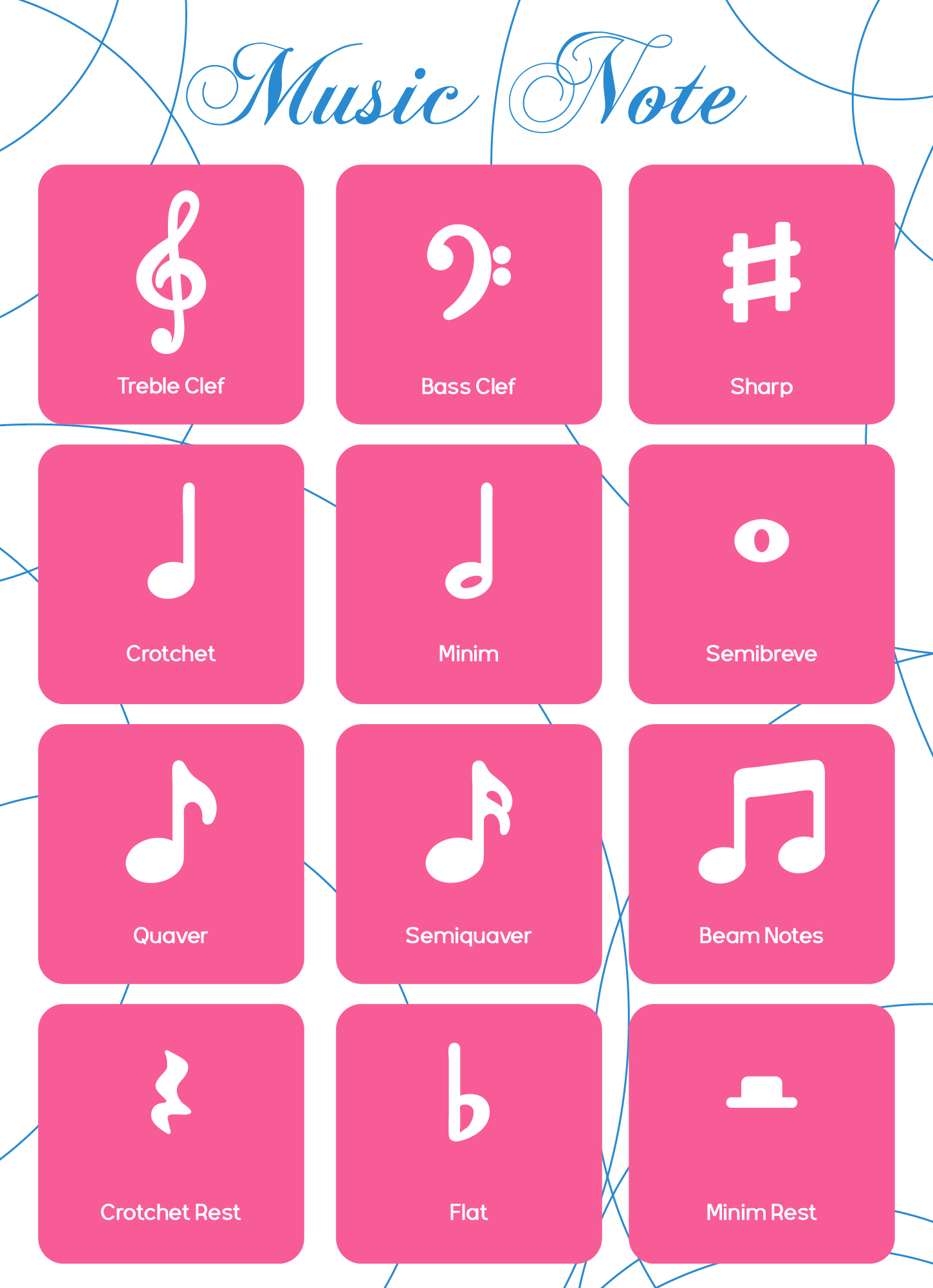

Printable Music Notes and Symbols

Printable Music Notes and Symbols

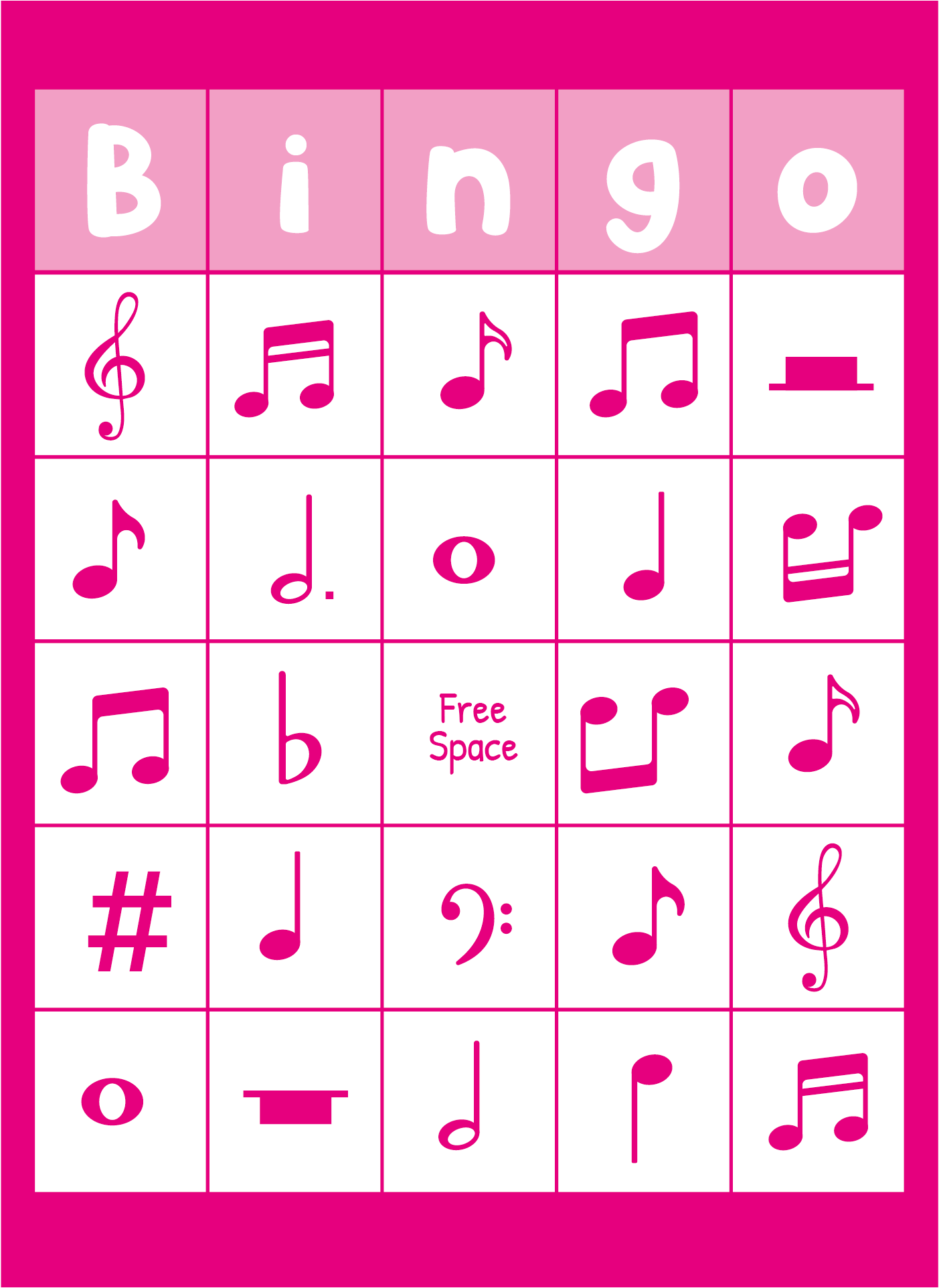

Printable Symbols Music Note Bingo

Printable Symbols Music Note Bingo

Art Clip Musical Music Notes

Art Clip Musical Music Notes

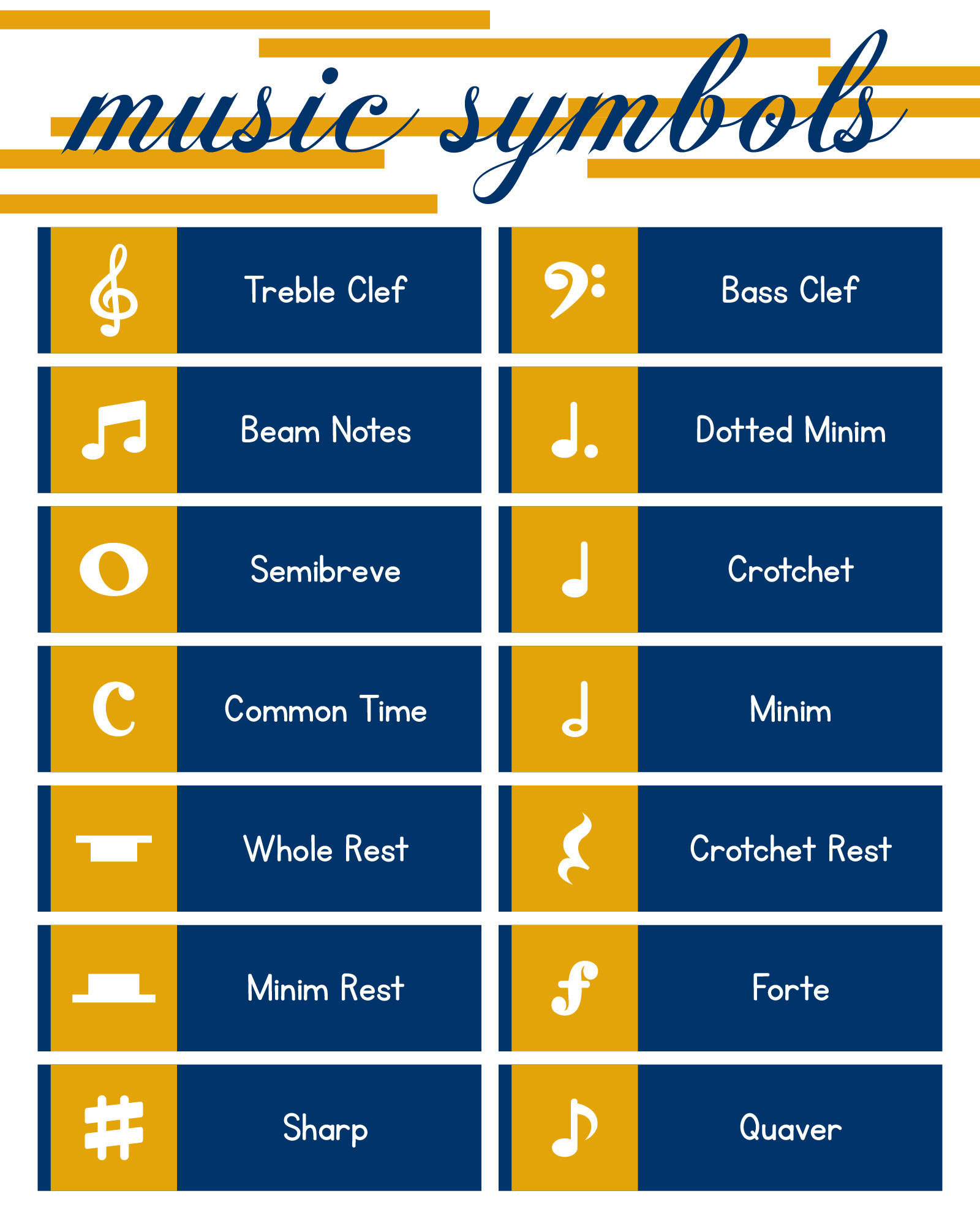

Basic Music Symbols Chart

Basic Music Symbols Chart

Music Notes and Symbols Montessori Materials

Music Notes and Symbols Montessori Materials

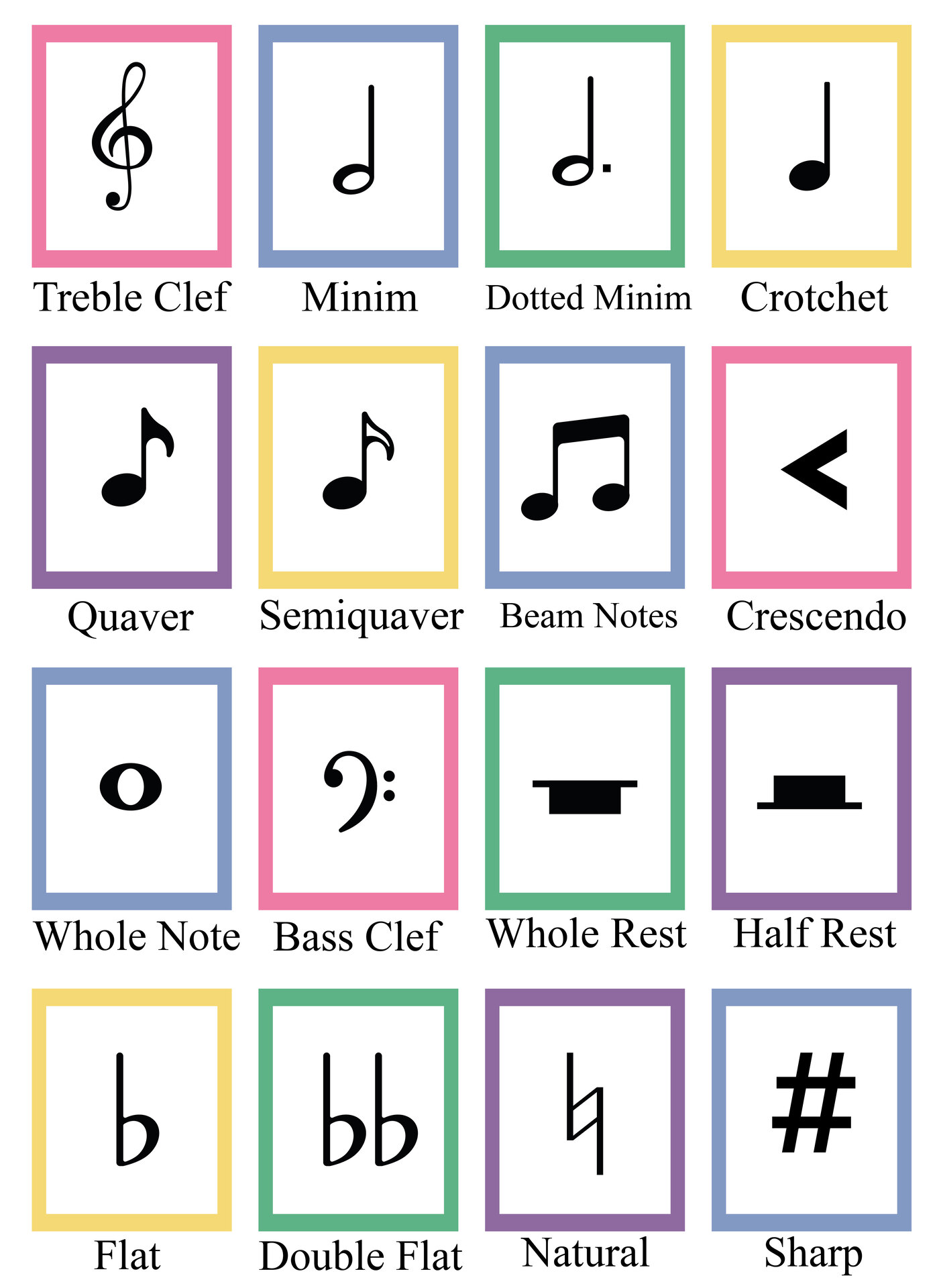

Music Symbols Printable Flashcards

Music Symbols Printable Flashcards

Cheat Sheet Music Notes Chart Poster

Cheat Sheet Music Notes Chart Poster

What are the Music Note Symbols You Need to Know?

In general, there are 11 music note symbols. However, there are 4 main music note symbols that you need to know. What are they?

- Staff: This is a musical note symbol that is used as the body and structure in all musical works. It is an important basis in writing songs. Without staff, musical notation would be incomprehensible and confusing.

- Bars: Bars are used to separate measures on the staff. This is very important in arranging song compositions. Bars are also related to beats such as 4/4 and ¾.

- Notes: Notes are important elements for communicating rhythm and pitch for a particular note. Different notes are combined to create melodies and harmonies.

- Dots: Dots are elements used to change the length of notes.

How to Teach Children to Read Music Note Symbols?

If you look at the national music curriculum, children who learn music at the early stage (stage 1) must learn musical notation. That's because musical notation is an important element in music. Musical notation is the basis for making music.

However, teaching musical notation to children will always be challenging. It's like teaching them a new language. Children will have difficulty understanding the concept of musical notation, but repeated practice will help them master it.

So, how to teach musical notation symbols to children? There are 3 effective ways that you can do.

- First, say the names of the musical notes out loud while practicing. For beginners, you need to assign them to say the names of the musical notes. They need to practice it regularly, at least 2-3 times a day.

- You can also use flashcards. You can get musical notation flashcards offline or online. You can also make them by yourself. In using the flashcard, you need to show the musical note symbol on the flashcard. Then, ask the children to play the note and say the name of the note.

- Note name games can also be a great option. Games are the best way to introduce musical note symbols to kids and they will be motivated.

What are the Benefits of Learning to Read Music Note Symbols?

Learning to read musical notation is an important skill for children. By learning musical notation symbols, children will get the following benefits.

- Musical note symbols are an important element in learning music. It can improve brain power, memory, and language. In fact, early age music learning will help improve children's cognitive abilities which are useful for their future lives.

- Music also teaches children about discipline. This is because children must routinely learn the elements of music, including musical note symbols. With regular practice, children will have good time management and have a positive impact on their discipline.

- Music is a therapeutic medium. Children can freely express their feelings through music.

- When learning musical note symbols, children must communicate with music teachers. It will improve their social skills. They will have good communication skills. They will also find it easier to understand instructions.

- Musical note symbols require focus and analysis. With these two skills, children will develop critical thinking which is important for their daily lives.

What is a Symbol Music Note Printable?

Symbol Music Note Printable is a symbol of musical notes written on a sheet that can be printed. Symbol music note printable can be easily found on our blog. We have many symbols of music notes with attractive colors and illustrations so that our symbol music note printable is very suitable for use by children.

We ensure that children will not get bored when using this printable sheet. We also make it easy to understand for beginners. So, children can learn the symbol music notes easily using our printable music notes.

How to Use a Symbol Music Note Printable?

To use our symbol music note printable, you need to download and print it. First, go to our blog and choose the symbol music note you want to use. Then, download and print it.

After that, you can integrate the symbol music note into children's activities such as playing to recognize the symbol music note. Make the activity fun so that children can understand the concept of symbol music notes and apply it easily.

More printable images tagged with:

Have something to tell us?

Recent Comments

I really appreciate this Printable Symbols Music Note resource. It's simple, yet incredibly useful!

This printable resource on music note symbols is just what I needed to enhance my music lessons! Thank you for creating such a practical and visually appealing tool.

I love the simplicity and clarity of these Printable Symbols Music Notes! They are perfect for my music-related projects and very easy to use. Thank you for creating such a helpful resource!